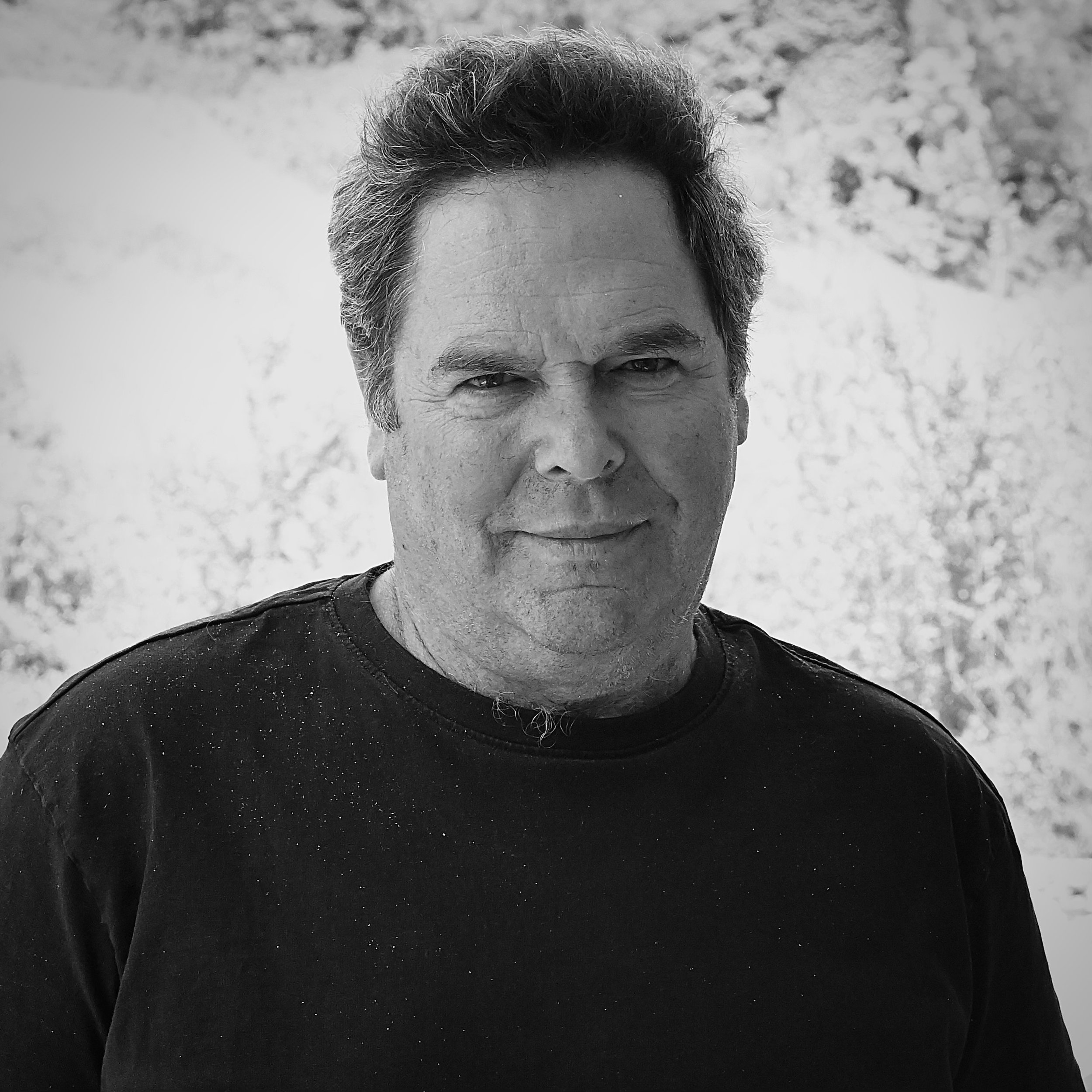

Peter Sahlins

Description: Peter Sahlins is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at UC Berkeley who now lives in France. His research looks at a variety of topics in European history from social and legal histories of nationality law and citizenship, to animal-human interactions and ancient paintings. The first part of the episode we talk in depth about his work on boundaries, and national identity. The second half of the episode we focus on Peter’s work on animal-human interactions from pigs standing trial for murder to Louis the 14th’s Grand Zoo. As we wrap up, Professor Sahlins sheds light on the “death of humanities” in American universities and how crucial it is that students develop critical thinking skills in their learning journey.

Websites:

Publications:

The Royal Menageries of Louis XIV and the Civilizing Process Revisited

Fictions of a Catholic France: The Naturalization of Foreigners, 1685-1787

Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees

Natural Frontiers Revisited: France's Boundaries since the Seventeenth Century

1668: The Year of the Animal in France

Resources:

Brent & Keller’s photos from Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte in Maincy, France

Show Notes:

[0:00:02] Introduction and Background of Professor Peter Sahlins

[0:03:42] Meeting Natalie Davis and Decision to Pursue History

[0:06:13] A New Approach to History: History from Below

[0:09:21] Folkloric Protests: Sophisticated Peasant Rebels

[0:13:12] Symbolism of Disguise in the War of the Maidens

[0:14:43] The Role of Women in Peasant Society

[0:26:57] Military Engineers as Ethnographers in Rural Communities

[0:28:12] Introduction to James Scott's books on domination and resistance

[0:34:01] National identities in borderlands and complexities of modernization thesis

[0:37:13] Critiques of national identity as a monolithic and totalizing concept

[0:42:13] Border Claims and Contentiousness Beyond the Pyrenees

[0:46:59] Transitioning to Immigration and Naturalization

[0:52:42] Restrictions and disabilities faced by foreigners in France

[0:58:02] Religious Minorities and Naturalization Process

[1:01:52] The Dissolution of the Disability of Property Inheritance

[1:10:45] The Absence of Animal-related Trials in the Literary World

[1:15:12] Animals in the Context of Cultural Shifts in 1668

[1:19:30] Transformation of the State and the Cartesian Universe

[1:24:13] Evolution of Louis XIV's Zoo: From Birds to Wild Beasts

[1:27:15] The Influence of Versailles and the Zoo's Destruction in French Revolution

[1:32:17] Descartes: A Frenchman or Not?

[1:35:20] Lecturing on Cartesian Physics and Blood Circulation in Paris

[1:40:20] Exploring the Oldest Cave Paintings and Transition from Middle to Upper Paleolithic

[1:44:19] Discussing the leading theory for the end of Neanderthals

[1:45:14] The debate on the end of the Neanderthal species

[1:53:07] The Shifts in the Humanities and Declining Enrollments

[1:57:20] The Crisis of the Humanities in the University

, Professor Peter Sollins, journey, chance encounter, historian Natalie Davis, prominent figure, history, research, empowerment, women, peasant society, complexity, identity, animals, Libraries Without Borders, decline of humanities, academia, gratitude, knowledge, experiences

Edit Transcript Remove Highlighting Add Audio File Stop Play-on-click

Save Editor Export HTML Export PDF Export WebVTT Export... ?

Transcript

Introduction and Background of Professor Peter Sahlins

Brent:

[0:02] Welcome, Professor Peter Sahlins. Thank you for coming on today.

Peter:

[0:06] Thanks, guys, for coming down to see me here.

Keller:

[0:08] We'd love to start off by hearing a little bit more about your story, how you got to Cal, and how you ended up in France.

Peter:

[0:15] Love to share some ideas or thoughts. It's actually the reverse.

It's how I got to France and then to Cal. So I did spend part of my childhood in France.

My father was an anthropologist and he had come to work and study at the university here and brought the family over.

This was in the mid 60s right before 1968, in fact.

And so I went to public school and I learned French and I lived here for three years.

Went back to the States, grew up in Michigan, Hawaii, Chicago, like that, but preserved this sense of a second identity, which is really what France was for me.

I never thought I'd become an historian. It wasn't part of the plan.

I did follow my father into the university, but I wasn't sure what field I would take.

And it was really an accidental encounter with a very important historian of what we call early modern France by the name of Natalie Davis, that led me into the field of history and eventually then into a job at Cal, at Berkeley.

So I hadn't studied history as an undergraduate. I never took a single history course.

[1:33] I did, however, in a course on popular protest and rebellion.

And remember, this was the early 70s, mid-70s, and the memory of 68 was still very much alive.

[1:46] I had taken a course by a sociologist by the name of John Bostad.

Who introduced me to a rather strange set of events that happened to take place in a historical period in France in the 1830s, which went by the name of the War of the Maidens, or the War of the Demoiselles.

And it was a story of young peasant men who, protesting the imposition of a national forest code in 1827.

[2:16] Disguised themselves, at least partially, as women and went out into the forest at night and chased off charcoal makers and forest guards.

Salamanders, they called them, because of their uniform.

And it fascinated me. It was a story of protest, but it was also a story of carnival, of celebration.

It spoke to me in ways I didn't fully understand.

And I was fortunate enough at the time to get a grant that summer, I think it was the summer of 1977, to come over to France to work in archives.

Remember, I had no training as an historian, no experience in history, and there I was working in archives.

It was a strange time, at least compared to today.

Could smoke in archives, for example, drink in archives, and they would, you would ask.

[3:13] The staff would just bring out these boxes of old papers. It was kind of an unbelievable experience.

So I started digging around and found all these reports, political reports, judicial trials, all sorts of other information.

And eventually pieced together a thesis, an undergraduate thesis on this.

Again, without any historical training or background.

Meeting Natalie Davis and Decision to Pursue History

[3:42] So, fast forward a few years, and I'm looking to go to graduate school, and I have this thesis, and I'm thinking about my father's field, anthropology, I'm thinking about archaeology, I'm thinking about sociology.

Sociology, and I go to Princeton with a copy of this thesis that had been in part, the interpretive scheme had in part been inspired by Natalie Davis, this historian of early modern France who had written about carnival and popular culture and festive rule and things like that.

And I met her and thanked her for her inspiration, offered her a copy of the thesis.

She looked at it.

She said, what are you doing? I explained my indecision at the time and she said, but this is a work of history.

[4:35] You should be an historian. And she sat me down in her office with a typewriter, remember, no computers and no mistakes possible, and told me to type out an essay to come to graduate school and study with her.

And I did. And I did. And there I was.

And I became an early modern historian. So, I tell you this long anecdote because it really underscores the role of accident, of contingency. and career choice.

We can dream as children that we wanna do one thing or another.

[5:17] Often enough, in the end, it's the people we meet, the places we go, the adventures we take that set us off into one path or another.

And we need to always be open to those ideas.

Then, of course, I looked for jobs. And I found a few one-year things here and there, up and down the East Coast.

And finally, in 1989, got a job at Cal. And I stayed there for 30 years.

A New Approach to History: History from Below

[6:13] So, yeah. The social movements of the 1960s and 70s were very much on everybody's mind.

[6:22] And when faculty, especially younger faculty, were encouraging us to really try to understand history in a way that when they had been trained and their teachers had been trained hadn't existed before.

We call it globally a kind of history from below.

So, popular culture, the history of popular protest, the history of everyday life, the history of ordinary people, not the stories of kings and queens, and not the story of states seen from above and international relations, but really the history of how people lived.

Lived and it was important at the time also to for all of us to acknowledge to borrow again the words of the british novelist lp hartley that the past was a foreign country that people did things differently then it wasn't about going into past times to find resemblances it was really about going to look for differences.

[7:29] And what I learned in graduate school with Natalie Davis, among others, was not only about the differences, but also about the different possibilities that the historical periods had presented, and the different set of choices, and the way in which people of different kinds and social groups and identities empowered themselves.

[7:54] In different ways. So, yeah, I think that possibly, as the son of an anthropologist, the appeal of the past being a foreign country took root.

Certainly growing up, both in France and in Ann Arbor, Michigan, university town epicenter like Berkeley of of the 60s and early 70s social protests that that part of things stayed with me.

And I sought to work that out.

In this particular case, it was interesting for me because a lot of the scholarly interpretations at the time of popular protests.

[8:41] Would dismiss these kinds of folkloric manifestations Manifestations and Protests as Primitive.

That was the title of Eric Hobsbawm's book, Primitive Rebels.

It wasn't as sophisticated as modern politics.

It was sort of an early infancy of political awareness.

But I was struck by how sophisticated, in fact, these peasant rebels were and how thoughtfully in some way they deployed, they made use of their own folk culture and identities to engage in a protest like that.

Folkloric Protests: Sophisticated Peasant Rebels

[9:21] So, I think that's what finally attracted me and stayed with me as it resonated over the years.

I never fully finished with that story.

It was an undergraduate thesis. It became my second book.

I tried to write a novel about it. That didn't work out so well.

I thought about a screenplay. It's a story that sort of 40 years, 50 years later now stays with me still.

Brent:

[9:51] Have you seen any works of fiction or inspiration about that story before, like a screenplay or novel?

Is that story well known?

Peter:

[10:02] In France, it's pretty well known. There were, in fact, a couple of films that had been made of it.

But at the time in 1830, it had come to popular awareness, collective consciousness, as a play in Paris, long distant from the Pyrenees, in which in a very different milieu, a middle class milieu, it was turned into a kind of romantic tale of a cross forbidden boundaries between a forest guard and a pilgrim.

But it had over the years produced a fair amount of fiction and drama and eventually film.

In the 70s, it was very much rediscovered as part of the recreation of local identities in the south of France and in the region that was at the time called Occitania.

And where people began in the aftermath of 1968 to develop a real consciousness of being different from Paris.

And I think that that also is partly what inspired me to stay and work in the Pyrenees after a while and where I started my dissertation that eventually became my first book.

Keller:

[11:30] And within the writing process, you mentioned trying to write a novel, and possibly a screenplay, could you talk about how writing history pieces in academia, how that process involves some degree of storytelling, and how that kind of weaves in to the actual process?

Peter:

[11:44] Yeah. And again, I learned so much from my mentor in graduate school, Natalie Davis, who was so insistent that as historians, we need to tell good stories, and that we need to think about them, but that as historians as opposed to novelists, our stories are held in check tightly by the voices that we hear in the archives, that we can't just make them up as we think they would be.

And it's a kind of constraint that's ultimately productive. It doesn't, so much limit us as offer us a set of possibilities. So I think good history really is about listening to the voices in the past and engaging with them dialogically, in dialogue with them, and then telling our own stories, but keeping those voices in mind and present to us, so that we can be true to them and not to betray them as such.

Keller:

[12:58] And then touching back into the War of the Maidens, could you talk about, you mentioned the carnival aspect, could you talk about a little bit what the symbolism of the disguise was as well as my understanding the war wasn't violent, right?

Symbolism of Disguise in the War of the Maidens

Peter:

[13:12] It wasn't violent. It was violent in the repression.

The military and police had produced one or two deaths on the part of the rioters.

It was a very symbolized violence, a very symbolic violence like that.

Brent:

[13:31] Pause.

Peter:

[13:33] I'm sorry, I forgot what we were, you said, we were talking about the violence, but right before that.

Keller:

[13:42] The role of the disguise.

Peter:

[13:44] Right, okay. Okay, so the disguise was curious because they didn't really try to disguise themselves as women.

I mean, this was not cross-dressing, this was not transvestism as such.

It was a theatrical production, as it were.

They basically took out their long white linen shirts and put a kind of belt around them.

And it kind of looked like a dress then.

The Role of Women in Peasant Society

[14:43] So, it was also very performative that they were deploying this kind of image as a kind of cultural resource to make a statement and a claim.

And a lot of the book was an attempt to make sense of what that claim could be by trying to understand the role of women in peasant society in the 19th century in a region which was strangely, in fact, almost singularly.

[15:15] Privileged by its empowerment of women. Women were heads of household in this region.

They had rights to inheritance that couldn't be found elsewhere in France, and there was a strong tradition.

There were also traditions about femininity that ranged from beliefs that we call folkloric or mythic about fairies in the forest and the supernatural powers that they they might have over men, to, as I tried to explain in a more anthropological way, to the very gendered idea of the forest itself, the forest as a woman.

And the kinds of techniques that were then used to exploit the resources were very much in keeping in line with this thinking of the forest in gendered terms.

[16:12] So, the symbolism and the metaphor of women was multivalent.

It had a lot of different reference, and it was only by entering into the cultural universe of peasant society in the mid-19th century, which itself was a challenging task because peasants don't write about their own society, and the people who write about it don't belong to it.

So, again, the question of voices and of translations and so on.

So it was only by penetrating into that symbolic universe that...

[16:50] That I was able to make some educated guesses about the significance of the disguise itself.

One thing was very clear, and it's something I argued throughout the book, is that we think of disguise and of masking in very instrumental terms.

That is, people wore a disguise or a mask in order to avoid detection or in order to symbolize their participation in in a group or association like that.

But it was very clear from the descriptions of the rioters that they weren't really masking their individual identities.

They would paint their faces with charcoal or sometimes with red okra and wear headdresses and so on. But again, it wasn't Halloween.

It wasn't going out and trying to hide who they were.

Keller:

[17:45] Yeah. And do we know why that particular region had a more feminine-focused society?

Peter:

[17:54] We don't actually. It's a curious question. It's not a particular valley or region.

Overall, we think of the Pyrenees as a site where historically, patriarchy of course, It's almost universal, but its force was somewhat lessened like that.

Why that should be might have something to do with elevation, and here I follow the lead, although not directly, of the great French historian Fernand Braudel, who associated...

[18:39] Mountain elevations with liberty, with freedom. And it's true that the Pyrenees and the Alps and other mountain ranges tend to be less directly within the purview of dominant civilizations, coming from the plains, the church, even empires and states like that.

So they tend to be more preserves of alternative modes of social organization that are not necessarily tracking as closely anyway, the norms and traditions of, in this case, patriarchy that sort of come from the valleys.

Brent:

[19:24] That's very interesting. I've never heard it described that way.

But do you think the War War of the Maidens and like that introduction to men like playing with their identities.

And then also you kind of experiencing the idea of like an American and a French identity.

Is that what led you to studying identities in like your career?

Peter:

[19:48] It's a good question. I often ask myself some version of it as I go through life.

Sometimes I feel like no matter what I choose to write about, whether it's.

[20:01] Peasants in the Pyrenees or Animals, which is the subject of my previous book, I'm kind of writing the same book over and over and over.

What do I mean? I mean, a lot of what attracts me to history and to French history is in part an approach that's, shall we say, oblique.

I'm interested in the question of identity but never as something taken as a thing in and of itself rather always as something that's considered in relation to, in reference to and often in opposition to other identities so this was the story of my work of the boundary and the borderland and the Pyrenees where I was really keen on understanding the development of national identity, not sui generis, not as an entity or a thing imposed by Paris on the peripheral provinces, on the distant Pyrenees, but as something that was generated in the borderland by peasants and other inhabitants of rural society as a way of differentiating themselves.

So one became French by not being Spanish in that sense.

[21:28] And that doubleness of identity was always present.

So I took that object lesson, as it were, and I studied the history of immigration and the history of French nationality law and French citizenship.

And it was always following the same kind of logic, that to fully understand the articulation and development of these categories, of these concepts, of these practices, one had to understand how they were constantly being mediated by their opposites, sometimes implicit and sometimes explicit.

One became French so that one was not a foreigner, a German or a Spaniard or an Italian, coming in like that.

Ultimately, if we're putting me on the couch psychoanalytically, yes.

I mean, it's part of my own sense of being in France and being an American in France, of having a kind of doubleness to my identity. but also of, We'll pause here because I'm not sure what I want to say, actually.

We'll just end it on the identity, that sentence there.

Keller:

[22:55] Yeah. And before we go deeper into the identity stuff, you mentioned the difficulty of working with peasant societies because they're often not literate and you're kind of piecing together other people's views on them.

Can you walk us through that process and how you navigate trying trying to visualize or tell the stories of these people when they often weren't able to articulate their own stories?

Peter:

[23:19] Yeah, it's one of the great challenges of studying not just rural society, but popular societies more generally, popular culture more generally.

It's a little easier in the 19th century than it is in the 16th and 17th century because by the 19th century, we have these so-called folklorists, these movements of educated middle-class people who go out into the countryside and who start collecting folktales and fairy tales and songs and dances and other forms of cultural expression of peasants and other rural inhabitants.

And even those that get collected in the early 20th century are often tales that are recorded by people who were born in the 18th century, or at least whose parents were born in the late 18th century.

So we have a kind of genealogy of these stories and folktales and cultural expressions like that that goes much deeper. Yeah.

[24:32] Such enterprises of going out and listening to the voices of the people were not unknown in the 16th and 17th century.

There were a number of people more isolated than later who did undertake those things. And those are very privileged sources.

We think of those as important.

But there are lots of other sources when we begin to disentangle them and even to deconstruct them.

We can begin to hear popular voices mediated and shaped but not completely silenced by the archives.

So judicial archives, for example, are an exceptional source for trying to understand popular attitudes, mentalities, beliefs, values, and so on.

When people go on trial, they tell stories, and the way they tell stories are, of course, contextually organized and constrained and so on, but at the same time, you know, coming from somewhere, and it's the coming from somewhere that we listen to very carefully.

So judicial archives overall tend to be important sources for the study of popular culture.

[25:59] And then administrative sources, including the sources of repression and so on, it sort of depends to a great extent on where one is studying like that.

Brent:

[26:16] Mm-hmm.

Peter:

[26:18] So, for example, in the borderland, it was quite astonishing because it was a borderland in the 17th century or in the 18th century, a few straying sheep across a supposed border generated massive amounts of documentation about local pastoral practices. practices.

And this went up the chain all the way to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

So I could go to Paris or to Madrid and sit in the foreign ministry and call up these narrative accounts of.

Military Engineers as Ethnographers in Rural Communities

[26:57] Local pastoral practices in the rural society in the Pyrenees.

Just, you know, unbelievably so.

So it turns out that military engineers were really good ethnographers.

They were really sort of apt at listening to local voices and recording them and trying to make sense of them like that.

So, you just have to be creative, imaginative, and constantly aware of the ways in which sources filter voices, but also enable them in those ways.

One more anecdote. So, I have a career long debate with the great political scientist Jim Scott of Yale who became quite famous for his understanding of rural society everywhere, peasants and wrote such important books as, blanking here so uh.

Introduction to James Scott's books on domination and resistance

[28:12] Give it a google yeah i'm just trying to get the title of it right, james scott um uh seeing like a stat no seeing like a state no it's earlier stuff against the grain no that's again earlier uh domination of the art domination the arts resistance you know and then one more. Weapons of the Week, that's right.

So James Scott, who wrote such important books as Domination and the Arts of Resistance or Weapons of the Week, in which he would consistently argue, and we would often argue in public, about what the job of peasants was or is.

He would always say, "'It's the business of peasants to stay out of archives.

[29:01] And which makes it nearly impossible for us to grasp and understand what they're after.

And I would make the argument, based on my work in the Pyrenees especially, that while it's not entirely false, there's also part of the job of a peasant is to get into archives.

And to take advantage of the resources of the state or of a local administration to empower themselves with whatever's available around them.

And that could be, in fact, the state. So, while we do think of peasants always as trying to hide from the state, it's also important to stress that in many contexts, people make use of the state for their own ends and purposes.

Brent:

[29:52] And that's what he means by getting out of the archives. It's not being involved in like state activities and like that.

Peter:

[29:58] Right. Of resisting at every turn and foot dragging and lying and subterfuge and all sorts of ways in which avoiding being identified, being registered, being counted, being taxed, being policed and so on.

And I think it's, you know, largely true, but it also, if we take it as a kind of global truth, then we miss the part about rural society, about peasant society, which is also strategically and instrumentally engaging with relations of power and authority in order to try to, again, improve their own condition. Yeah.

Brent:

[30:44] And then could you build off of that in relationship to the Pyrenees and how those locals were trying to establish their identity both locally and nationally?

Peter:

[30:55] Yeah, so that was the basic thesis. So, again, when I started the project in the 1980s, the dominant paradigm at the time was a kind of modernization thesis that, first of all, that peasants, in order to become Frenchmen or Spaniards for that matter, had to lose their peasantness, had to lose their local identities, their local sense of place, their local practices, their local language and customs.

And so on and so forth, and to adopt something foreign, something imposed from above.

And that nation building was about capital cities and political elites going out and imposing a national culture on local society.

So it didn't seem to work that way, because when I started digging in archives, I started finding in the municipal archives and local archives among peasants who were at least representing other peasants and local institutions.

[32:01] I began finding claims of attachment to these supralocal entities, France or Spain or whatever.

And the declaims were often made in a language that was neither French or Spanish.

It was, in this case, Catalan, because this was part of Catalonia.

[32:28] And it was often made in the context of also utter continuity in social life across the border.

Or pilgrimages, intermarriage, even agriculture, people who own lands on both sides of the border.

And yet in certain cases, and they happen to be, I began to notice more and more cases involving, contestation over local resources, a river that runs from one side of the border to another, or pasture land that's owned by one community across the border like that.

And for us, in many of those cases, people, peasants, members of rural society were actively empowering themselves with these national identities to say, no, it's mine, or it's ours, and it's not yours.

So, you know, we know from Marx and way back about the idiocy of rural life and the way in which peasants are always fighting over the fruit tree on their boundary and so on, but, and that doesn't, you know, it's a caricature and so on, but there's some obvious truth to it, but it also doesn't stop people from doing so, as Frenchmen or as Spaniards.

[33:47] In opposition to each other, especially if that fruit tree is all of a sudden not just on a neighbor's property, but it's in Spain.

Think of the possibilities, right?

National identities in borderlands and complexities of modernization thesis

[34:01] All of a sudden you can start to use that language, a very powerful language, increasingly powerful in the 18th and 19th centuries, use that language to make your own local claims.

And without ever losing your own identity in the process like that.

So, it was that business of what happens in a borderland that got me going and allowed me to, as it were, kind of scale the interpretation to think more generally about how people come to adopt national identities and how the whole modernization thesis was really misleading.

Leading, because here in this village and elsewhere, people became French without stopping being peasants, or stopping being members of the local community and so on.

And identities just got more complex and worked at different scales and became contextually more interesting and relevant, but it wasn't about replacing one identity with another.

Brent:

[35:14] More just like adding it on.

Peter:

[35:15] It was adding on and also then...

And strategically deploying in a kind of very instrumental way.

You know, a lot of the critics of my work said, oh, well, these were just masks that people would wear.

You know, they wore the mask of Frenchness in order to advance their own interests.

And my response, even in the book, was that it's true. That's how it starts.

You start by wearing the mask of French, you know.

But the mask ends up being really sticky.

Brent:

[35:48] Yeah.

Peter:

[35:48] You know, it kind of sticks to the skin after a while and pretty soon it's kind of hard to take it off.

You don't need to take it off because you can also still be a member of local society and so on.

And then when you need to, you can claim that legitimacy as a Frenchman or a Spaniard like that. that.

Brent:

[36:09] Do they believe that identity is like singular than the critics of your work?

Because it seems relatively straightforward to me, at least that identity is very fluid and you can have a bunch of different identities and switch between them, have multiple on at the same time, whatever it may be.

Peter:

[36:28] But the fact that they said that you have to have one or that one was a facade, odd like what what is their idea of identity so you know i think that you're speaking from a position that's much more um you know sensitized to this than 30 years ago i i think that that that we do have that we have evolved from from modernization theory in that way still it's It's also important to underscore that often when scholars and critics and everyday people start talking about national identities, it almost becomes a thing in and of itself.

Critiques of national identity as a monolithic and totalizing concept

[37:13] And this has to do with the way in which the ideologues of nation made national identity into such a totalizing thing.

[37:23] Form of identity that deliberately had to become more important than family identity more important than local class identity more important than communal identity and had to have this kind of privileged place i mean this is what you know fascism and authoritarianism totalitarianism state communism that was part of the tactic and strategy of the great ideological movements of the 20th century so there are echoes of that in the scholarship that continue to this day in which it's often believed, that the kind of monolithic totalizing quality of national identity doesn't permit its coexistence and articulation with other identities.

Now, what I try to do is shift the conversation a little bit and to think of identity really as a contextual process and one in which its articulation is not just a universal constant.

[38:38] But rather has to be understood in its particular manifestations as both an instrumental and an effective claim but one, in which the claims at one moment, at one time, are not the same as in others, and that context is everything like that.

Keller:

[39:03] Yeah, certainly. And within the contextualization of particularly like a boundary, can you talk about why the Pyrenees were so unique?

And how, I believe we're talking about the boundary set up by the Peace of the Pyrenees, and how that was the most stable or one of the most stable boundaries in Europe at that time, and how having a region that its boundary didn't shift consistently.

Whereas if you look like Prussia, for example, constantly shifting definitions of boundary or regional boundaries, how that really helps with the contextualization.

Peter:

[39:36] Sure. I mean, I think it helps and hinders in some important sense.

So, what I mean by that is that yes, the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659 establishes the Pyrenees as a natural frontier between France and Spain.

And I've written about this separately, but it's a very powerful metaphor of a natural frontier.

It has enduring significance, not necessarily as an accurate description, because if, in fact, we look at the boundary, It doesn't really always follow the crest of the mountain range, and it's often very difficult to establish watersheds as the exact boundary like that.

But it's a powerful tool, and ideologically it served really important purposes, especially for the French state, especially for the official...

[40:36] Expression and a development articulation of national identities.

So, the Pyrenees are kind of special in that way.

But it's also important to note that while the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees establishes the watershed as a natural boundary of France and Spain, the actual demarcation of of the boundary, that is laying down the border stones to show actually where the boundary is drawn, doesn't happen for another 200 years.

And that period between 1659 and 1868, when the delimitation is finished.

[41:18] Suggests not as fossilized a boundary as political geographers and others would make it out.

In fact, it suggests a fairly highly contentious process. Now, imagine that you don't have a natural frontier.

[41:38] Imagine the frontier of France in the north and east, in which there are enclaves and exclaves of foreign authorities, sovereignty, lordship, in which there is no natural marking like that.

I mean, the same phenomenon that I'm talking about in the Pyrenees is even accentuated and aggravated by the absence of commonly agreed-on natural features of the landscape that divide like that.

Border Claims and Contentiousness Beyond the Pyrenees

[42:13] So the claims in a borderland, in that sense, are even louder in areas outside the Pyrenees, in the north and the east, and also even in parts of the Alps than they are in the Pyrenees.

So the Pyrenees, in that sense, especially after the delimitation in 1868, may have quieted down as a border in that way.

But the phenomenon that they reveal as part of a natural boundary are more universal to border situations more generally.

Brent:

[42:56] And then how long did it take after the boundaries were set for the local citizens to start adopting the national identities?

Because I would imagine it could be very wrong, but at first...

When governments draw a line, they still feel like they're neighbors.

So I'm more just curious about, like, at what point do they really start to divide?

Peter:

[43:21] It's a good question. So, I mean, I do treat this in the book.

It's very important to think of this in terms of developmental stages like that.

And there is a moment for about 60 years after the Peace of the Pyrenees where the frontier is still highly militarized.

And this is the period of the wars of Louis XIV until really his death in 1715, in which it's still a contested frontier with Spain, in particular.

[43:53] In this case, and in which military forces of one side or the other are constantly themselves crossing the boundary.

And one can only imagine, and the archives suggest as much, that it's not conducive to the kind of process that I was describing for about the local empowerment using the boundary like that.

So, the Wars of Louis XIV come to an end in 1715, and it's really at this moment that we begin to see the first articulations of national identity.

It's interesting that one of the first evocative expressions or set of expressions across the board occurs in 1720 and 1721, which is the moment of the arrival of what we now know to be the last incidence of the Great Plague in Europe in 1720. Right.

[44:57] This is a story which all of a sudden becomes very familiar to us because of our recent experience with COVID-19.

But all of a sudden, the states instantly define their borders as part of what they called at the time a sanitary cordon that seals France off.

[45:17] And so the Pyrenees become, it's less of a military imposition of authority than an attempt to really differentiate.

So the moment of the imposition of the sanitary coordinate, people who, you know, have interests on both sides of it and properties often or use rights or access to the forest or attempts to access waterways and so on, begin to then, what should we say, articulate and to express and to take, as it were, conscious possession of this kind of thing.

Of distinction and make use of it for their own purposes.

So the brief answer would be yes, sometime in the early 18th century, you begin to see these kinds of expressions.

And again, for the scholarly literature, that was a bit of a revelation because nobody really thought that in the 18th century, country peasants would wear the hats of a Frenchman or seek to claim national identities like that.

Brent:

[46:28] And then wearing the hat of a Frenchman, is that just more saying like of Parisians?

Was that like what controlled all the French identity at that point before like the rest of the periphery really took on that identity?

Peter:

[46:45] Could you try that again, that question?

Brent:

[46:52] It might not be worth it.

Keller:

[46:54] Yeah, we can...

Brent:

[46:55] We can just skip that because...

Peter:

[46:56] Okay.

Brent:

[46:57] Yeah.

Transitioning to Immigration and Naturalization

Keller:

[46:59] I was going to take a quick break. I think we're going to transition to immigration law and then do foreigner stuff in terms of naturalization.

Peter:

[47:08] All right. Is that a good transition? We can sort of drop the border story altogether and just talk more broadly about immigration and naturalization.

Sure. Yeah. And if you want to move it forward, because we're going to, we have to get to animals.

Keller:

[47:23] Yeah.

Peter:

[47:24] And then prehistory. Yeah.

Keller:

[47:26] Okay. So then building on, you know, with boundaries and national identity, along with that comes immigration of people into new nations.

Could you talk about your work studying the history of immigration law and the development of naturalization?

Peter:

[47:42] Absolutely. So I became interested after the publication of Boundaries in 1989, which was, of course, a world historical year in and of itself.

And my book actually came out November 9th, which was the day that the Berlin Wall fell.

So Boundaries was a timely publication in itself.

But I became interested in the movement of people more generally across boundaries in the 1990s, and the debates that started to rage, especially in France, about national identity, the first real crisis of French national identity, which took place, you know, in the late 80s and early 90s, like that. And.

[48:37] There were editorials in the major newspapers and elsewhere about really sort of declamatory proclamations, really, about what French identity was.

You know, it's based on a birthright, or it's based on descendants, or, you know, just really very ahistorical kinds of claims.

And my instinct as an historian was to be more skeptical and to seek to complexify the story.

So I became more and more involved in both the double history of immigration, of people moving into France, and of nationality at a time when the term nationality didn't even exist.

And so that raised immediate questions of what did it mean to be French before the arrival of the nation state, which we identify with the coming of the French Revolution in 1789.

What did it mean to be French before 1789 when there was no constitution.

[49:42] There was no legislation, there was no statutory identification of Frenchness, there was instead a kind of vast jurisprudence.

And as I dug into this history of law and jurisprudence, I started to note that there was a lot of lawyers in particular were making hay with the claims about French identity, that he is naturally French or he is not naturally French.

My book eventually became called Unnaturally French, which was a way of pointing to these debates and to suggesting some of the ways in which and strategies of the foreigners coming into France actually sought nationality.

So, to make a long choice short, it became apparent, and the more I read, the more I discovered a history I had never learned before, not in school, obviously, because I hadn't studied history, but even in the literature at the time.

Which was that while there wasn't any constitutional or statutory way of identifying Frenchness, there was an important and complex and robust way of identifying foreignness.

[51:02] And here we go back to the same theme that seems to haunt me in my work throughout my life, that is the only way to really understand Frenchness in this way is by understanding what it meant to be foreign.

And what it meant to be foreign in this case was the subject of...

[51:23] Both a political and a legal effort to identify the disabilities of foreigners living in France.

And these disabilities actually stem from the feudal period, the 12th and 13th centuries.

But beginning in the 15th and 16th century, they became redeployed by the French state as a very ultimately muscular way of marking the distinction.

Keller:

[51:53] By disability, do you mean like the removal of quasi-rights?

Peter:

[51:57] Well, so the principal disability that foreigners had in France, starting in the 15th and 16th century really, for the entire country, was the inability to either devolve or to inherit property Okay.

Restrictions and disabilities faced by foreigners in France

[52:43] Couldn't pass that property to his children unless those children were, unless he was naturalized or the children were naturalized.

So there were other disabilities attached to this that came and went with the political climate often, and so were much more dramatic in times of war.

Sometimes the foreigners were banned from holding public office or the like in the church.

Foreigners couldn't hold benefices, which are the material goods attached to their religious office, unless they were naturalized.

So, what became critical in the identification of foreigners, in the identity of foreigners, was the set of disabilities.

What became critical in becoming French was the naturalization process.

So, we're not talking about a mass scale of naturalization.

Naturalization, as we know it, as a modern phenomenon, doesn't begin until the 1880s and 1890s, but I did spend...

[53:55] A solid 10 years going throughout archives all over France, especially in Paris, but all over France, looking for the judicial registries and the political registries of naturalization.

And I did find, I can't even remember now, something like 6,000 or 7,000 of these over the course of the database went from 1660 to 1789.

So, on average, maybe 50 or a few more a year of these.

And again, it pales in proportion to either the real number of foreigners in France at the time and to the population in general, but it was still, even though statistically insignificant, it was an important way of trying to make sense of French identity.

By looking at these foreigners, where they came from, what their professions were, where they settled in France, and so on, and being able to map all that out for the first time, which had never been done before.

So in two books, one of which I co-authored with a young French historian at the time.

[55:22] Jean-Francois Dubost, and in a book that I published in 2004 called Unnaturally French, part of the effort there was just really, besides all the interpretive work that was done, was documentation.

I mean, this was the first time that anyone had really made this effort to count, not so much to count the foreign population, but to at least count the population that sought naturalization. Mm-hmm.

Brent:

[55:55] So what was that naturalization process like back then?

Peter:

[55:58] So oddly enough, it was fairly automatic, meaning that there wasn't a lot of discretionary judgment exercised in the royal chancellery and in the political administration of the crown.

[56:15] There wasn't a lot of denial of naturalization. So, you know, if people basically went through the fairly rigorous and somewhat costly process of getting a lawyer and of pursuing the demand and so on, there were very few kind of statutory requirements and even fewer cases of people who were denied naturalization.

So surprisingly for me there was no for example loyalty oath i expected to find some kind of affirmation and despite the fact that there was and there was no litmus tests of culture so you didn't have to necessarily speak french or you don't be french in that way culturally speaking that didn't stop people in their petitions from claiming those things that i'm french because my My grandfather fought in the wars, or I'm French because I've lived here all my life, and I married a French woman.

People told stories, and again, we get back to judicial archives, where the stories of people, not so much peasants in this case, but ordinary people, often get revealed and get incorporated into a kind of standardized text about demand for naturalization.

Brent:

[57:32] Mm-hmm.

Religious Minorities and Naturalization Process

Peter:

[58:02] And did not recognize religious minorities, Protestants, the handful of Muslim and the rather large populations of Jews in the country.

And there was a kind of Catholicity clause that became prevalent, if not privileged, within the naturalization process. process.

Interestingly enough, though, members of these religious minorities, in collusion with state authorities, found lots of ways around this.

There's a great story that I told in this book about the Jews of France, for example, who in the 18th century, they, were increasingly identified as foreigners, and foreigners who were not Catholic and therefore could not apply for French citizenship.

[59:11] Well, the 18th century was an interesting period because it was a period in which this practice of citizenship that I just described of naturalization was evolving rapidly, And in which the imposition of restrictions and prohibitions on foreigners was gradually and then somewhat radically loosened in the 1750s so that the disability of foreigners in property terms, the right to pass down property to their own kin, was actually eliminated in a series of bilateral treaties between France and the rest of the European countries in the 1750s and 1760s like that.

So, this is the context in addition to a kind of resurgence of anti-Semitism on the part of the law courts in which a few families, but an important set of examples, starting in the 1760s and 1770s, said in basic terms, or would have said if we had been able to interview them, and said, oh, you think we're foreigners?

[1:00:35] Well, if we're foreigners, then we can petition to become French, especially when, at a time, the restrictive clauses were being abandoned.

And all of a sudden, more than a dozen French families became French citizens long before the emancipation of Jews in 1790 and 1791 in France.

So it's, again, this example of the ability of people, even in positions of domination and so on, find ways to strategically move through these things and take advantage of the resources, read the context, and make hay out of difficult circumstances like that. Anyway, so.

Keller:

[1:01:25] And was the major dissolution, did that come from the Edict of Toleration, or is that a separate time period?

Peter:

[1:01:32] I'm sorry, did it come from?

Keller:

[1:01:33] The Edict of Toleration?

Peter:

[1:01:36] No. I mean, the Edict of Toleration initially ended the French religious wars at the very end of the 16th century, so 1598.

And then the withdrawal of that edict was 1685 under Louis XIV.

The Dissolution of the Disability of Property Inheritance

[1:01:52] And then the abolish the abolition of the um disability of property inheritance which we haven't given a name to it was actually called in english a right of a sheet uh for those who might know english law because it was actually important in in the development of english nationality as well um that was uh reciprocally um, dismantled between France and the European powers in a series of treaties that went from about 1750 to the French Revolution to 1789, like that.

So they really were not in relation. The toleration and the abolition of the right of a sheet were separate entities.

Keller:

[1:02:45] Yeah.

Brent:

[1:02:46] Yeah.

Peter:

[1:02:47] Is there anything else about how identity and like nationality was like formed that you think that people should be aware of whether it be french or elsewhere in the world that how nationality that comes to be and maybe how that's influencing even present day ideas of nationality um sure yes i mean i do think it's important again And that when we think about something as complex as the history of nations and of nationality, that we think beyond the kind of usual, shall we say, bipolar debate that has informed most of the scholarship and a lot of the popular discourse about nationality.

The bipolar debate, and I use that term tongue-in-cheek, is either that nationality is something that has always existed as part of a deeper, atavistic, primordial, maybe even autochthonous creation, and that is...

[1:04:05] He finds expression as a kind of pot boiling over when political authority is removed or in situations of crisis.

You know, the way in which a lot of people talked about nationality during the Balkan Wars in the 1990s like that.

These are, you know, the Serbs and the Croats have always hated each other.

Without going back 50 years at a time when there was something called Serbo-Croatian language and culture, right?

And one of the great pieces of literature of the 20th century about nationality, Ivo Andrić's Bridge on the Drina was written in that language.

[1:04:49] So that's one side, the sort of atavistic side.

And the other side, in relation to that, and it's opposite sometimes, you know, nationality is just simply something that's created from above and that's forged and formed in kind of constitutional moments like that and then imposed on people.

We've rehearsed this argument already.

We've seen it in modernization theory like that.

So, you know, I think my work just, in this context and more generally, speaks to the need to complexify our understandings.

And I think if I were to scale that thought more generally, I think that's what we do in history.

And as historians, whether we practice professionally or not, not just to take Hartley's phrase again that the world, that history is a foreign country, they do things differently, but really to...

[1:06:00] Appreciate the complexities of historical processes and to study them, to learn about them, to think about them so that when we ourselves are faced as we are often enough today in moments of crisis, our reactions are thoughtful and not just knee-jerk and not not in that sense programmatic or ideological going forward.

History is about making us think more and harder about how complicated the world really is.

Brent:

[1:06:38] Yeah, definitely.

Keller:

[1:06:39] Important message. Then transitioning a little bit, we want to get into your work studying animals.

Could you start us off by just telling us what inspired you to take that focus?

Peter:

[1:06:51] Well, again, to sort of reprise the comment before, so I came to study French identity by looking at its obverse or its opposition to others.

And so I started in some ways scaling that same method and thinking about the historical question of what makes us less human, not as an exploration of human nature, but as the way people thought of it at different historical moments.

And I started thinking, well, you know.

[1:07:38] Transcending the boundaries of humanity, looking at the animal world, looking at how people thought about the animal world, that that could allow me some insight into how people, and still in this case French people, thought about what it means to be human.

The real story of how that book, which was called 1668, The Year of the Animal in France, how that book originated is a little more curious.

So after I finished with immigration, nationality, citizenship, and all that, I was kicking around, as historians often do for a topic, waiting for one to choose me, because that's often the way we work.

We think we choose topics, but in the end they come and find us.

[1:08:31] And when we connect, then it's gold. But I started getting really interested in echoes of what I was noticing around me in the early part of the 21st century as a kind of animal moment.

It was at a time when the animal rights discourse was really pervasive and when one began to see animals appear where they had not long had a place or expression, that is, in the world of art, in particular art exhibitions, in literature and so on.

And I remember that as a graduate student, I had found fascinating once the story of these medieval animal trials, that is, trials of either domestic ordinary animals.

[1:09:29] Dogs pigs and the like or of insects that were actually put on trial not so much in the middle ages but actually in the early modern period that i studied in the 15th and 16th century put on trial for crimes against humanity funny story right but so they but it was an entirely entirely serious judicial process.

They were actually a pig who had run loose in the village and had ate a baby, was captured, put on trial, given an attorney, put into the jail cell, and then put on public trial, and generally but not always convicted and put to death, right? Right.

So I thought, what a great story. You know, this is the topic has found me.

I'm going to call this book Animal Wrongs.

And I'm going to write this book. So I started writing this book.

And like several very important and even more knowledgeable historians before me, I gave up because there was no record of anything. We talk about voices.

The Absence of Animal-related Trials in the Literary World

[1:10:45] None of the judicial trials were there in part because a lot of these trials were also for the crime of sodomy or bestiality, as we call it.

And the trial records were destroyed as part of the purification that took place at the end of the trial. but even though those that weren't, the trial records weren't kept.

And so what bothered me the most was that there were very few echoes of these trials in the learned literary cultured world.

[1:11:25] Of elites in the 16th century.

There was one example of a group, In the 16th century, with a jurist became famous for defending a set of worms that had eaten the Bible in the town of Autun, which is only an hour from here in Burgundy in 1540.

But other than that, there were no echoes.

[1:11:54] Except one. So the famous playwright, tragic playwright Racine, produced this play in 1668 that was based on Aristophanes, the Greek playwright's piece called The Wasps, in which the third act was an animal trial, was the trial of a dog that was put on trial and ultimately released, found not guilty, for eating a rooster, well, a castrated rooster, a capon.

[1:12:40] But it was all done in a comic spirit and it was all sort of making fun of the magistracy and so on. Still, something resonated with me.

68, he's making fun of something in 68.

What else do I know about 68? 1668, we talked about 1968, but here's another 68.

And then I thought, well, you know, I know that that's the year that the great literary writer, Jean Lafontaine, produced his fables, right?

Which are animal tales woven into moralistic narratives like them.

[1:13:25] So, I think that the internet played a really important role in this because I was able to cut transversely in databases and sort of just search out 1668, sort of what happened in 1668.

And I found this astonishing number of animal-related events and stories.

And whether it was debates about Descartes' animal machine, whether it was debates about the blood transfusions of the medical doctor Jean Denis of animal blood into humans to cure disease and to prolong life, whether it was in literature in 1668, whether it was in tapestry in the decorative arts, whether it was everywhere, there were echoes of this.

And I literally hunted down those animals.

I tracked them back, and they all came from the Royal Menagerie, Louis XIV's zoo, which was the first garden pavilion built on the grounds of Versailles and finished in 1668.

Brent:

[1:14:36] Huh.

Peter:

[1:14:37] So, huh. is right. That was the idea, right?

So, all of a sudden I said, well, there's a story that can be told, right?

And it's a story of how and why Louis XIV built this zoo, and what happened to the animals that literally either escaped for it, sort of metaphorically speaking, but more likely that just died and their bodies were then recycled in a kind of symbolic afterlife.

Animals in the Context of Cultural Shifts in 1668

[1:15:12] And why so much attention was being paid at this particular historical moment to animals?

Why was 1668, like the early 20th century, an animal moment?

What was going on in terms of the broader cultural shifts in this society, political and cultural, that made animals so important and meaningful at this moment.

Keller:

[1:15:39] Yeah.

Brent:

[1:15:40] So what were some of those reasons?

Peter:

[1:15:44] So, I mean, I identified two major transformations transformations that came to really be articulated in this pivotal year.

So one was the construction, the building of this new kind of state in France by Louis XIV, the state we call absolutist, and the way in which...

[1:16:17] And the way in which the king and his courtiers, his architects, his natural historians, his garden landscape architects, garden architects, the way in which all these different groups actually made use of animals and animal figures in the construction of royal authority.

And it had very much to do with the novelty of the kind of symbolic or, if you will, even poetic expression of the state in the 17th century, built very much with animals in the gardens of Versailles.

So that was one sort of important transformative moment.

And the other was the arrival and the awkward reception of the Cartesian universe and all that it implied from the perspective of what we think of now retrospectively introspectively, as a kind of desacralization of the world, the development of a Cartesian physics.

[1:17:40] The idea of blood circulation and the secularization of the human body, and so on.

And a lot of those debates about Descartes were carried in the concept that he developed already in the 1640s in discourse on method, of the animal machine.

I'm going to, you're going to pause that.

Brent:

[1:18:14] Sure, yeah. Okay.

Peter:

[1:18:17] Of the animal machine and the animal machine was this idea of animals as automata it was the idea that the animal body is just a machine and in its exaggerated form you know the cries of the dog and pain are just the wheels of the cogs that are screeching together and that there is no consciousness consciousness, no soul in animals.

And this was a way for him of being able to articulate something about the distinctiveness of humans who had a soul and therefore a dualism between their mind and their body as opposed to animals and part of the rest of the material world which was literally devoid of soul.

And of course this was an important rupture with the whole inheritance of the view of the cosmos that came from Aristotle and the view of the human body that came from Galen and so on, and the whole radical revolutionary break.

And it all happened, or so I thought, in a somewhat conceited way in 1668.

That is, it all came together.

Transformation of the State and the Cartesian Universe

[1:19:30] So this transformation of the state and transformation of the cosmos cosmos, could be traced.

[1:19:38] Could be elaborated as part of the deeper background that helped to make sense of why animals were so good to think, as the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss had put it in 1668, using animals to think about these different broader political and cultural transformations.

Brent:

[1:20:03] So, do you think by putting them in captivity, it was justified almost by the fact that they don't have souls? Or...

Peter:

[1:20:16] Not really. I mean, this wasn't the first time that animals were put into captivity.

In fact, there was a long princely tradition, not just in France, but throughout Europe and indeed globally speaking, whether it's ancient China or pre-contact Mexico, of keeping animals, and often animals given as tribute, as part of a symbol.

And sign of domination and of global reach, as it were, like that.

There were a number of distinct, and secondly, it wasn't so much that the Cartesian worldview was adopted or present by everyone in 1668.

It was an idea that was debated, and it wasn't necessarily by any means informing the thinking thinking that went into the creation of the menagerie.

That said, the Royal Zoo of Louis XIV had a number of novel and distinct characteristics.

[1:21:27] One was the idea of taking all the king's animals and putting them all in one place in a form of animal spectatorship that was very distinctive because his royal architect design this garden pavilion that actually was the precursor of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon built or conceived, you know, 150 years later, in which from a central place.

[1:22:05] The spectators could look over the separate courtyards of buildings as it were gazing as a form of control over the different Korg ads which were divided by species.

That part was novel and, Distinctive. The other thing that was distinctive is that Louis XIV, at least in the beginning, kept the wild animals out of it, the wild beasts out of it.

So the lions, the tigers, the bears, which actually were kept at the Chateau of Vincennes on the eastern side of Paris, the complete opposite side of Paris than Versailles, which is outside on the western side of Paris.

[1:22:50] Louis XIV, when he was just a child and under the tutorship of his Italian preceptor and first minister, Cardinal Mazarin, had built this arena for animal combat in which wild animals would tear each other up and so on.

It was a complete disaster.

[1:23:19] It didn't work. It was a total failure as a kind of show.

Nobody liked it. It was not in keeping with tune, in tune with the times and customs and so on.

And it led to Louis XIV, when his tutor died, turning his back on that model of animal spectatorship and building instead in the Garden of Versailles.

This is a very peaceable and peaceful collection made up largely of large migratory birds, flamingos, storks, egrets, swans, the like.

And it was these animals whose wings were clipped so as they would be kept in open cages that were the principal denizens, if you will, of Louis XIV Zoo.

Evolution of Louis XIV's Zoo: From Birds to Wild Beasts

[1:24:13] Now later things evolved, the bears came back, the lions came back, by the 18th century it was a kind of modern zoo as we knew it and in fact, you know.

[1:24:25] Including the popular classes, would come out in chariots, horse-drawn carriages from Paris on the weekends to go to the zoo, very much in anticipation of modern or at least of 19th century practices.

But at the time, it was in those two senses novel.

Keller:

[1:24:49] And I know that Versailles took a lot of inspiration from Baudivicon.

Was the zoo Louis' special touch to what could be seen as very identical architecture of the building itself?

Peter:

[1:25:03] Yeah, so it's a great question. And if you go to Vaux-le-Vicomte, which I'd urge your listeners to do, because it's really one of the gems of late Renaissance of classical architecture, and certainly far less touristed than the halls of parks of Versailles.

So Vaux-le-Vicomte, which is southeast of Paris, about an hour out, was built by the then finance minister of Louis XIV.

[1:25:42] And it is filled with animals. everything from the squirrels sculpted onto the walls of the outside.

The finest mystery was a man by the name of Nicolas Fouquet, and his personal armorial, his personal heraldic shield was a squirrel.

And the motto was, you know, how high he can climb in Latin.

And so he put squirrels everywhere, he decorated the ceiling with animals.

He did everything with animals, but he didn't build a zoo.

And so when Louis XIV came and took power, he not only threw Fouquet into prison and so on, and not only took under his employ all the architects.

[1:26:43] And sculptors, painters, and the like that had helped to build Vaux-de-Vicombe were then turned loose, as it were, in Versailles.

But he also, for reasons of his own, decided that he was going to take all these animals and instead of decorate the walls and ceilings and columns and so on of the outside of the palace, And it was the first garden pavilion that was built long before the palace.

The Influence of Versailles and the Zoo's Destruction in French Revolution

[1:27:15] And in fact, the Menagerie, which has today been destroyed, and for intrepid visitors, armed with a map, which can be found in the book, you can go out at the end of the Grand Canal and actually walk the site of the old Menagerie, which has been turned into a farm and has never been excavated properly.

And a few of the walls are still remaining like that.

So he had, you know, Louis XIV had gone and built this pavilion, which then became a model for the palace.

So the Versailles itself was built or rebuilt rather, because it was an old hunting lodge.

[1:28:03] Rebuilt by the architect Louis Laveau, whose first effort was the garden pavilion of the zoo and later elaborated it into the palace we now know of as Versailles.

Brent:

[1:28:16] Why was the zoo destroyed?

Peter:

[1:28:19] It was destroyed in the French Revolution.

And it was destroyed in part because the metaphor was so resonant to people at the time that it was too obvious, as it were, That the king had, as a despot, had ruled over these animals the way he had ruled over the people, and it was no longer tenable.

It had become such a symbol of the aristocracy itself. Yeah.

Brent:

[1:28:53] That makes sense.

Keller:

[1:28:54] And then before we transition to your current work, I'd love to hear a little bit more about, you mentioned Descartes, a little bit more about his influence in France at that time, and also a little bit about the culture of salons.

Peter:

[1:29:06] Of salons?

Keller:

[1:29:07] Of salons.

Peter:

[1:29:08] Of salons, yeah. So, you know, as I mentioned, Descartes was a figure who died in 1650.

So, but, and who in his lifetime was already a much contested individual in his works were, you know, at times banned and censored by the law courts in Paris, eventually by the Pope and the like.

And who was much debated.

At the same time, he worked in so many fields and so many different disciplines, as it were, so that you can track the importance and debates over his ideas, whether it's in physics or astronomy on the one hand or in medical history and study of the body on the other.

And tracking them at the reception at different rates and different times in different ways.

[1:30:24] He published in 1634 Discourse on Method, which was a hugely important book because it really taught people a number of different things, including to trust their own authority and not necessarily to rely, ironically, on books, other people's books, to think reasonably, to think clearly, clear and distinct ideas was the catchphrase.

Also, the book introduced the idea of animal automism and the like.

So, on the one hand, in salon culture of the middle of the 17th century, which was in many ways a conservative culture and not where cutting-edge ideas were necessarily being thought out, We don't think of the salons in the 17th century as the kind of experimental laboratories of philosophy that they became in the 18th century during the Enlightenment period 100 years later.

They were often very conservative places. On the one hand, you know, Descartes and the Cartesians were often, you know, anathemized, rejected by their, while at the same time, Cartesian ideas like clear and distinct thinking.

[1:31:46] Were embraced. So, the reception of Descartes is complicated.

It's not an either-or proposition.

There are parts of Descartes that were very much embraced and others were not.

[1:31:59] But nor was it a kind of Cartesian movement.

When Descartes died, he died in Sweden in the castle of Queen Christina, where he had spent one too many long, brutal winters.

Descartes: A Frenchman or Not?

[1:32:17] He was ailing physically, not that old, and he died, and that was that.

And it was in the next 10 or 15 years that his acolytes created a kind of cult of Descartes and attempted to kind of reinvent him as not just a good Catholic, but a good Frenchman.

It's ironic because Descartes spent most of his life outside of France.

He was born in France, but he was not comfortable in France.

He was much more comfortable in the northern countries, including the Netherlands and ultimately Sweden, which had more developed, what should we say, cultures of toleration than France did, especially in the 17th century.

So after he dies.

[1:33:17] Actually his brother-in-law goes to Sweden, collects his papers, they start this big campaign to put Descartes back on the map, but also to really present him as a respectable figure.

And this gets a little bit, what should we say, there was pushback, especially on the part of the judicial establishment, but also on the part of the Pope who puts all of Descartes' works on the papal index until proven, until corrected is what the Latin says.

It wasn't a universal condemnation of all of his works.

It was like, you know, stuff is not quite right, needs to be corrected.

So this is the context in which that.

And a lot of the debate from the point of view of the church was about how to reconcile this Cartesian worldview with the miracle of transubstantiation that happens in the Catholic mass when the piece of ordinary material wafer gets turned into the body of Christ.

[1:34:30] And so this is the debate about Descartes. In 67 and 68, the debate shifts and explodes, and it shifts away from transubstantiation, and it moves directly to the animal question.

And, you know, everything, it's like a shift in registers that happens.

And it's the year that, in 1667, that Descartes' body is brought back to France, by a group of like-minded philosophers, including the young student Jean Denis, who is then going to undertake the transfusion experiments with animal blood in a Cartesian spirit like that.

Lecturing on Cartesian Physics and Blood Circulation in Paris

[1:35:20] So there's a big pilgrimage, if it were, were a procession to rebury Descartes' bones.

And there's a whole book that's been written about Descartes' bones that's really quite lovely, but to rebury Descartes' bone in the church that's now next to the Pantheon in Paris, Saint-Étienne du Monde.

[1:35:46] And it happens. And so Descartes there now is in Paris, and then this guy, Jean Denis, along with other people, well, they start going out into the salons and they start lecturing.

And they start lecturing on, you know, Cartesian physics and how, you know, it kind of displaces the Aristotelian, worldview and they go start lecturing on blood circulation and they start, you know, and people, it becomes a real sort of fashionable event to go and hear these lectures.

[1:36:22] Hitherto, like when the great comet comes in 1665, the comet becomes an event and people, and now it's Descartes' animals and people go to the lectures and they listen.

So it's in this context that the menagerie gets built and that the animals are again sort of let loose in Paris and Descartes' animal automatism, the animal as machine becomes one more figure on which to think about and debate the question of this new world view that's not fully accepted by everybody.

You know, the Paris law courts will, the Paris Medical School, it's gonna be 30 more years before they finally adopt blood circulation as a reality like that.

So there's still resistance, there's still pushback, but the breakthrough is really in 1668.

Brent:

[1:37:25] I think that actually very well tied up the animal side of your research so could you maybe go into a little bit more of what you're doing now in France?

Peter:

[1:37:39] So I retired, or rather I separated from the university in 2019 and moved to France, I've done several things number of things since then.

I put in a plug here for a nonprofit that I was part of in its founding in 2007, and I'm still very actively working for it called Libraries Without Borders.

We deliver access to books, information technologies, and cultural resources in situations of humanitarian emergency and otherwise.

We actually are very active nowadays in the U.S., Libraries Without Borders U.S., helping public libraries in public outreach and in creating library spaces in trusted local neighborhood institutions.

We pioneered putting libraries into laundromats nuts throughout the US and now we're contracted with library systems anyway. So I spend a lot of my time, Working in that, I've been involved in museum work, including a show at Versailles a year and a half ago that was actually based on the book I did on animals, a show called The Animals of the King.

[1:39:09] And I bought a house in Burgundy in the countryside that happened to be the same village where the world famous caves of R.C.

Sirocuro the name of the village can be found it's not why I ended up in this village but it was again the role of hazard happenstance and it was a fortuitous fortuitous event um i've had a long engagement uh with archaeology as a reader and also my father had been very interested even though he was an anthropologist we spent a lot of time in archaeological settings visiting um i went on digs when i was a child lived in hawaii did a lot lot of archaeology there.

I thought I might become at one time an archaeologist.

So that was all preparing the ground like that.

The caves in our sea are amazing.

Exploring the Oldest Cave Paintings and Transition from Middle to Upper Paleolithic

[1:40:20] It's not just that we have right next door here what are really the oldest cave paintings in France and indeed possibly in Europe that date back 30 to 32,000 years ago.

[1:40:41] But also that site of these caves is one of the most important ones for understanding the transition, as it's called, from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic, something around 35,000 years ago.

[1:40:59] When modern humans, anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, arrived on the continent from Africa through the Middle East and began to settle across the European continent, displacing in ways that we still don't understand the pre-existing Neanderthal populations, which became extinct.

These two populations, again, humans and Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, more than likely coexisted in these caves, in this village, as it were, which therefore has a history that goes back not just that far, but well into the earliest Neanderthal settlements about 200,000 years ago.

Brent:

[1:41:51] Mm-hmm.

Peter:

[1:41:53] At the same time, these caves have been known forever, not forever, but at least since the Romans, who threw coins into the lakes and pools inside the caves that we found in the medieval period where people actually lived in the caves.

And really since the 17th century where both scientists and tourists have been visiting ever since.